Under the open slats of venetian blinds, and against the darkness outside, a lone man shines a light on the tense intimacies of urban life. Even in the ostensible privacy of their own homes, people in dense cities are so often on view.

Sitting next to an open window in Brooklyn, the shirtless man leans forward, his focus keenly directed towards something that the viewer cannot see in Roy DeCarava’s Man in Window (1978/1982). The gleam on his face, shoulders, and beer can suggest the halo of a television screen. But framed entirely by the window, the man instead presents as the quintessential pensive figure à la Rodin’s The Thinker, but his preoccupation eludes us. The viewer looks into the man’s home at night, while he looks into a space that we cannot access—the world of the screen, his room, and his own thoughts.

Another night, another threshold of public and private space. A sensuous work of requited longing.

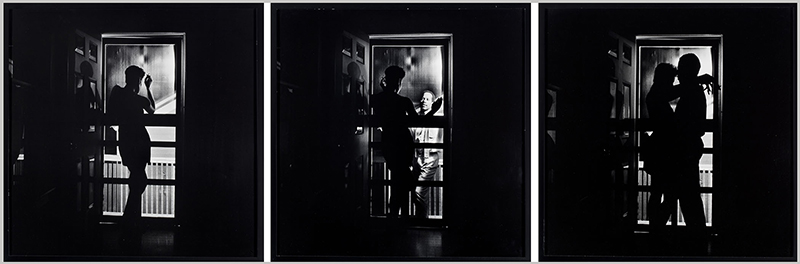

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Black Love), 1992, Gelatin silver prints. Smart Museum of Art, Gift of the Estate of Lester and Betty Guttman, 2014.831.1-3.

Carrie Mae Weems’ triptych Untitled (Black Love) (1992) moves from a lone figure in isolation and into an intimate embrace, with its central female figure holding the power to welcome the “love” of the title indoors. With her back to us, the woman—Weems herself—stands at an entryway mostly in silhouette. Backlit through a screen door, she rests her elbows on its surface while her body forms a subtle S shape, waiting, watching. In the second photograph, we see a man brightly lit standing on the other side of the door. The woman’s hand approaches the screen’s edge, at the cusp of the decision to approve or deny entry. In the final print, the man and woman are fully inside together, in the space of darkness, standing in an embrace, her arms over his shoulders, his head gently touching hers. Together at last.

The darkness of the nighttime interior framing each photograph shrouds the subjects at its heart. At the edge of waiting and acknowledgment, they form a connection that creates its own world.

Amidst the coronavirus pandemic, these two works from the Smart Museum’s permanent collection have come to resonate in new ways for me on matters of attention, longing, and love. And their inclusion in the Fall 2019 exhibition Down Time: On the Art of Retreat has further prompted me to reflect on these studies of observation.

Last spring, the students in Exhibition in Practice, a course that I taught through University of Chicago’s Department of Art History, came up with an idea for a show centered on “down time.” Beyond leisure and pleasure, the exhibition explored the mechanisms that make it possible for people to take time and space away from extreme events and everyday life. The artworks revealed how shutting down can be a gateway to opening up—and how opening up might only become possible by stepping back.

Against 9-to-5 productivity and linearity, the exhibition and its related programs offered pausing, fuzziness, and meandering. The show reckoned with the ways that access to “down time” operates at the intersection of necessity and privilege. And further, that the experience of taking time can be differently available and experienced across the lines of identity and social conditions. Among its many conceptual touchstones, Sarah Jane Cervenak’s notion of “wandering,” Saidiya Hartman’s exploration of “waywardness,” and Sable Elyse Smith’s “ecstatic resilience” propelled our thinking. Together, we napped, danced, breathed, wrote poetry, colored, looked, and lingered.

Of course, none of us foresaw the moment in which we currently find ourselves with so many of us forced into “down time” in the confines of homes and temporary shelters as the result of a global pandemic. At the same time, so many of us are within those spaces and busier than ever, balancing remote work with childcare, working day and night to seek new employment and secure benefits, and wading through anxiety about the future. And then there are those of us working in essential capacities, overtime and with increased risk. In a world transformed—if only temporarily—by coronavirus, what on earth is “down time”?

Many of the central themes and provocations of the exhibition’s artworks potently anticipate this time—when minutes, hours, and days have found new configurations and rhythms that we struggle to follow. Clocks and calendars catalogue cancellations, delays, and postponements while “down time” reigns seemingly unbounded. But it is a “down time” distinct for its isolation; the need for social distance finds us inside looking out as well as outside looking in, longing to be together at last.