Get the Flash Player to see this player.

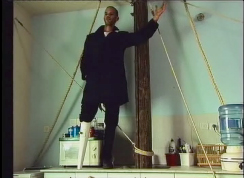

Excerpt from Guy Ben-Ner’s silent single-channel video Moby Dick, 2000. Courtesy the artist and Postmasters.

Get the Flash Player to see this player.

Excerpt from Guy Ben-Ner’s single-channel video Wild Boy, 2004. Courtesy the artist and Postmasters.

Excerpt from Guy Ben-Ner’s silent single-channel video Moby Dick, 2000. Courtesy the artist and Postmasters.

Excerpt from Guy Ben-Ner’s single-channel video Wild Boy, 2004. Courtesy the artist and Postmasters.

Interview: Guy Ben-Ner and Stephanie Smith

SS: Your two works in Adaptation are part of a larger group of videos created within a pretty consistent set of constraints. You’ve often filmed in or around your apartment, built simple scenery and props, used fairly low-tech equipment, and cast yourself and your family as performers. You initially set up those parameters in part as a creative response to your circumstances as a young artist and parent. By maintaining them over time, you’ve developed a recognizable style and a rich set of themes. Is that a fair assessment?

GBN: Yes. But what you call a recognizable style is just a byproduct. It is never something I aim for.

You’ve often adapted other works of art (Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick and François Truffaut’s film L’enfant sauvage (The Wild Child) in the works that you’re showing in Adaptation. Do you find that working with classic source material functions in a similar way to those other parameters? It seems at least in part like another way for you to set up productive constraints for your art.

That is correct but I usually have too many reasons for every decision I make. For example, in a gallery space, where viewers usually enter while the video is running, the classic source material helps them recognize where they are and what they are watching, if they know the movie.

What drew you to these particular sources?

I was attracted to narratives because I realized I needed to tell stories. I felt like I have learned at school how to break things but not how to create anything linear, any story. So, I decided to look at adventure narratives. They are also stories that both adults and children can enjoy, and I needed to engage both an adult and children in the process of making my movies. I wanted to stage an adventure at home: to turn the inside into an outside, to create a fantasy, and to find the minimum number of lures needed in order to set the fantasy going. I put Elia in the sink, and that was enough to turn the kitchen into a bar, and her into a barman. What happened was a collapse of a private family story into a cultural fantasy. A family photo album is quite similar: it is very private but it looks the same everywhere, because it is culturally dictated in many ways.

You’ve talked elsewhere about the fact that you didn’t read the novel Moby-Dick until after you started to work on the piece: initially you knew it as an iconic story whose themes and characters are pretty deeply embedded in Western culture, and then you got to know the text itself. With Wild Boy, you knew the film before you began the piece, correct? Do you think that matters?

You are right. Moby-Dick was something I read only after realizing I was interested in sea adventures. Before that I made my version of Robinson Crusoe and I had never read that book before shooting either. But I knew both stories like everyone else does. I was interested in Truffaut as a director who worked quite a lot with children long before I made Wild Boy. In this case I knew the source before setting to work with it. In his Wild Child, Truffaut cast himself as Doctor Itard. That made me realize that he was not really talking about taming a wild boy, but rather about a director who tames a child actor. That is why he dedicates the movie to Jean Pierre Leaud, his first child actor. That spoke to me. More than anything, I felt it was an account of a guilty man regarding his early sins: telling truth through fiction. But for me, to use a source I need it to connect to many things in which I am interested, not just one. It has to become a kind of magnet that attracts many ideas. Among other things Wild Boy also refers to Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book, to Buster Keaton working with his father Joe, to Dennis Oppenheim working with his kids, to Charlie Chaplin (the kid), Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Emile, and the idea of silent cinema as a wild child being tamed by language and sound. So I build this conglomerate made of all these power relationships and try to express my private life through them.

You structure some of those references as cameos: brief quotations that punctuate the videos. You include bits of imagery based on specific works of early cinema, Buster Keaton’s slapstick silent comedy, classic works of performance art. For those who know the sources, those cameos set up an intertextual play of references, but they also function as pleasurable moments within the work even without that extra layer of knowledge. Do you think it’s important for viewers to be familiar with some or all of your sources?

It is impossible to tell if anybody can really locate all the sources. Sometimes they are very well hidden. What is important for me is that, as a viewer, you realize you enter a territory that is made out of patchworks. That is something you can feel, I hope, even without knowing exactly what and where things came from. You can experience my movie as a very personal speech made out of other people’s words.

Critiques of film adaptations often focus on fidelity. The classic conversation is about whether or not a film is true to the book on which it’s based (true to specifics of the narrative, to key themes, to some ineffable sensibility). Do you think at all about fidelity in that sense? As an artist, it seems that even when you’re adapting a well-known source, you have more latitude to be loose.

That is because I use them as material. I use them to tell my private tale, a tale that is unable to escape cultural limits. I do not use myself to retell these narratives, I use them to tell myself. My obligation is to Guy Ben-Ner, not to Moby-Dick.

How did you use drawing to develop your ideas for these two works?

I made some drawings for these works, but do not use drawings anymore. I now realize I used drawings not so much to plan the movie as to be able to retain my thought focused on it while preparing. It kept my mind focused.

It was my first attempt to deal with the fact that my movies are screened in a gallery or a museum space: a space where people enter the movie in the middle. For me it is not so much an installation, but rather a viewing platform, a comfortable signal to viewers to stop, and take their time. And I tried to use it economically: the set itself becomes a movie theater.

Could you discuss sound? Moby Dick is silent, and you use sound and silence in very particular ways in Wild Boy

I am very careful with sound. It is a very powerful glue and I felt I needed to use it carefully. Only later did I begin to understand what can be done with it. It came on stage rather slowly in my work. Now it occupies a bigger space. And in the case of Moby Dick and Wild Boy it also has a thematic and generic side to it: the silent cinema and the child who does not talk.

What about those moments at the ends of the videos where you shift into another mode of storytelling: the scene on the subway at the end of Wild Boy, for instance.

I usually have a problem with endings. I never really reach conclusion. My endings are always a beginning of another story. In Wild Boy I use Amir, my son, or rather his small legs, to make myself look pitiful, to attract attention. This shot is actually a remark I make regarding the whole movie: yes, I use my children to attract attention. Funny enough Moby Dick also ends with my daughter functioning as my legs. Both endings are foot notes.