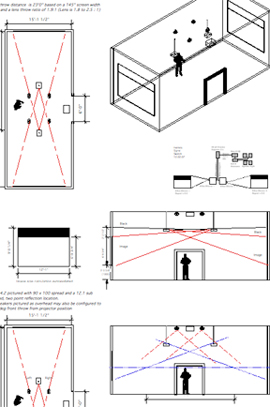

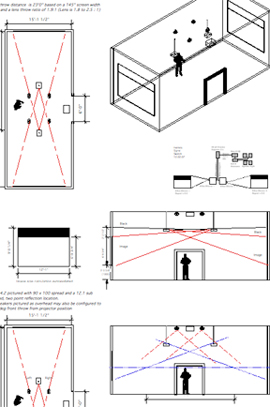

Larry Smallwood, Herrera Video/Audio Plan, Isometric, Elevations, January 2008

Kelly Kaczynski, “air is air and thing is thing”,

2005, courtesy the artist

Tilo Schulz, Remake of ‘Restless Ball’ by COOP HIMMELB(L)AU, 1971 by Tilo Schulz, 2002, 2002, courtesy the artist

Installation view, Arturo Herrera, Les Noces, 2007, photo by Tom Van Eynde

Installation view, Eve Sussman and The Rufus Corporation, The Rape of the Sabine Women, 2006, photo by Tom Van Eynde

Installation view, Catherine Sullivan, Triangle of Need, 2007, photo by Tom Van Eynde

Installation view, Guy Ben-Ner, Wild Boy, 2004, photo by Tom Van Eynde

Larry Smallwood, Herrera Video/Audio Plan, Isometric, Elevations, January 2008

Curator’s Introduction

High Fidelity?

Stephanie Smith

Director of Collections and Exhibtions, Curator of Contemporary Art, Smart Museum of Art

Adaptation presents work by Guy Ben-Ner, Arturo Herrera, Catherine Sullivan, and Eve Sussman & The Rufus Corporation, all of whom have transformed existing source material—classic literature, film, ballet, painting, even e-mail—into new works of art. (The Chicago presentation also includes a work by ARTV 24103, a group of University of Chicago students that produced a work for the show as part of a practicum taught by Sullivan.) The artists have chosen to explore their sources deeply rather than, say, briefly quoting from them. Yet they have substantially transformed the originals: pushing and pulling them through intuitive and analytic processes, adding many new layers of content, bending them to their own purposes.

These generative sources remain present to varying degrees in the final works of art, which prompts questions: Are these works faithful adaptations, and does fidelity matter?

The question of fidelity is raised in slightly different terms by another aspect of Adaptation: its focus on video installations, which are relatively malleable in relation to changing technologies and exhibition spaces. The exhibition presents a range of approaches to the genre. This choice reflects the varied ways that contemporary artists create and display video and also provides changes of pace as viewers move through the exhibition.1 We developed the Adaptation presentations in close collaboration with the artists, a process that revealed the varied degrees of control that the artists assert as their works move through different circumstances and are inflected in large or small ways by institutional limitations and desires.2 Since several of these presentations differ substantially from prior iterations of the work, the exhibition also offers an opportunity to consider what constitutes a faithful presentation of a video installation.

Fidelity: Part I

As I write this introduction, a slew of book-to-film adaptations fill theaters around the country. They range from big Hollywood productions like The Golden Compass and No Country for Old Men to ambitious smaller projects like Persepolis and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. Films like these comprise the most common and familiar form of adaptation, spurring countless post-movie conversations along the lines of “which was better, the movie or book?” Such discussions may take into account the ways that shifting from text to moving images and sound opens new interpretive possibilities for the filmmaker. They might also consider the differences between adapting a standard novel (like the first two examples) and less common sources such as graphic novels or memoirs (like the third and fourth). They probably assume that the adaptor bears a responsibility to honor the source by faithfully and extensively translating plot, character, and setting, or by expressing some crucial essence of the original’s sensibility. Certainly they will be shaded by each viewer’s familiarity with the source and by the expectations he or she brings to the film.

Variations on the movie-versus-book conversation have surely taken place for decades amidst popcorn-strewn theater lobbies, among viewers still dark-dazzled in the immediate aftermath of a screening.

(Now, less romantically, they also occur on living-room couches strewn with Netflix mailers and through e-mailed responses to YouTube postings.) Such debates have also consumed a great deal of scholarly energy. A few years ago, when I first began thinking about an exhibition that would address adaptation as a strategy within contemporary art, I shared the idea with my colleague Tom Gunning, a film scholar here at the University of Chicago. He was skeptical at first. In fact, the very word “adaptation” almost shut down the conversation. Adaptation studies, he told me, has generally been a conservative and under-theorized subfield centered on that most familiar mode of adaptation—novel to film—with much analysis focused on whether and how specific filmic adaptations are faithful to literary sources. He noted, though, that a growing number of scholars have been working on adaptation and fidelity in more complexly nuanced and playful ways.3

Some of this scholarship addresses ideas like intertextuality, a term coined by theorist Julia Kristeva in relation to literature to describe how in any text, the author generally makes reference to many prior texts, and the reader creates meaning in part through her knowledge of those specific prior texts as well as many others. The concept of intertextuality is now being used as a tool to understand adaptation both as a creative process and as a received creative product. New adaptation studies also investigate adaptive paths other than the classic book-to-film type. Adaptations take countless forms: film to novel, TV series to film, film to videogame, novel to opera, and myriad other complex transmutations.4 I took my title—“High Fidelity”—from a song by Elvis Costello. Nick Hornsby used it as the title for a novel, which Stephen Frears made into a film, which was then adapted into a short-lived Broadway musical. Such works may hew to their sources in a conventionally faithful way, for better or worse in terms of their success either as adaptations or as independent works of art. But like the most inventive film adaptations, the consideration of more convoluted, unexpected, or experimental adaptive paths open new ways of thinking about fidelity.

One of my favorite theatrical works, for instance, is the performance company 500 Clown’s adaptation of Macbeth. In this utterly contemporary production, only the barest bones of Shakespeare’s plot, mise-en-scène, and language remain. Instead, three kilt-wearing performers put themselves into serious and hilarious peril by scheming and striving for a paper crown: a cheap emblem of power suspended just out of their reach. In 500 Clown MacBeth, the group fearlessly jettisons many beloved elements of the classic tragedy, using a few core elements of the original as a platform from which to launch a new work of art that incorporates many new chains of reference, is marked by their own interests and aesthetic sensibility, and speaks to complex realities within our current culture. The works of art presented in Adaptation are aligned with this looser approach to source material.5

They are also aligned with a set of related practices within visual art. Many of the best-known historical works of art, for instance, depict mythic, historical, or biblical stories, condensing complex narratives into a single frozen moment.

More recently, a number of contemporary artists have used illustration, homage, re-creation, appropriation, remake, and reenactment as ways to engage deeply with earlier art or with historical events.

Extended meditations on prior literature and visual art, for instance, have grounded several important recent projects. In 2004, Zak Smith illustrated every page of Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 novel Gravity’s Rainbow and created an orderly, wall-filling display of the intensely drawn images.6 In Kelly Kaczynski’s critical homage to Marcel Duchamp, “air is air and thing is thing” (2005), a group of sculptures scattered across a room form an updated version of Duchamp’s infamous tableau Etant Donnés (1946–66) when viewed from a particular angle.

Mark Wallinger’s powerful sculptural installation State Britain (2007) meditated on a different kind of source. Within the gracious halls of Tate Britain, Wallinger re-created a messy, sprawling cluster of protest materials that an activist had accumulated as part of his long-term anti-war demonstration just off a busy street in front of the Houses of Parliament. The government removed the bulk of the activist’s materials, sparking public debate about protest and censorship. Wallinger meticulously re-created this material as sculpture with copies of everything from photocopies to hand-lettered signs to ragged teddy bears. His choice to faithfully re-create the original in a new context was powerful: it allowed extended contemplation of something most people could only have glimpsed through a car window and activated Britain’s museum as a space in which to probe the roles of citizens, artists, and institutions within the country’s political culture.

Many time-based works might also be considered as related strands of recent practice. It is common to incorporate existing footage into new film and video works through appropriation, collage, or new methods that radically shift the ways we engage in the original film. Douglas Gordon is the poster child here, with a number of film-based works following his celebrated 24 Hour Psycho (1993) in which he slowed down Hitchcock’s famous thriller so that a screening takes place over a full day. Other performative and video-based works make manifest a deep engagement with specific sources by re-creating prior performances or reenacting historical events. These include works like Tilo Schulz’s performance and video Remake of ‘Restless Ball’ by COOP HIMMELB(L)AU, 1971 by Tilo Schulz, 2002 (2002), in which he and a friend walked through a small town while enclosed within a plastic bubble; Felix Gmelin’s Farbtest die Rote Fahne II (2002), a remake of a short film documenting a 1968 activist performance in which his father and others carried a red flag through the streets of Berlin; and Jeremy Deller’s The Battle of Orgreave (2001), a reenactment of a 1984 battle between British police and striking mineworkers. In each case, the artists faithfully re-created core elements of the original—walking in a bubble, running with a flag and filming that sprint in a particular way, setting into motion a specific choreography of violence. They did not invent significant new elements or embellish the originals. Still, the inevitable shifts of time, place, point of view, and intention allow the artists and their audiences to consider their sources anew from a contemporary perspective.

These varied approaches—illustration (Smith), homage (Kaczynski), re-creation (Wallinger), appropriation (Gordon), remake (Schulz and Gmelin), and reenactment (Deller)—differ from adaptation as presented in this exhibition. To be schematic about it, all of these approaches involve the investigation of a specific source that is then updated through relatively small shifts in form, content, or context that introduce new aesthetic intentions and perspectives. The resulting works of art oscillate between source and response: much of the punch and meaning of the work is generated by the artists’ and audience’s capacity to consider the complex interrelationships between a thing (or event) made then and there, and a related but distinct thing made here and now. All the artists chose to accept the constraints of fidelity because it served their own purposes.7

The works in Adaptation are not so faithful. They vary in their approaches, but Ben-Ner, Herrera, Sullivan, and Sussman & The Rufus Corporation all use their sources as starting points for new video installations that do not rely on such a tight one-to-one correspondence between an original and a response.

As with the other works discussed here, the source offers a point of departure for the artist and point of entry into the work for viewers, but many others pathways come into play as well. Herrera maintains the closest connection to one source, for Les Noces is a beloved work of art and he wanted to spend significant time plumbing its depths, reconsidering it in relation to his own work, and using it as the prime generative force behind his first foray into moving images. Ben-Ner pursued a more open approach. He has described his process of using a key source like L’enfant sauvage as a magnet that has enough complexity and power to attract a catholic range of other material. Sussman similarly drew her initial inspiration from David’s painting The Intervention of the Sabine Women (1799) but quickly amplified that static image with a range of other sources, including the Roman myth on which David based his painting. Sullivan also takes several core generative sources and pushes them through layers of research and analysis that are further extended as her collaborators bring in additional sources and as her performers interpret the material. She has expressed some anxiety that foregrounding the sources within the context of an exhibition like Adaptation can overdetermine how viewers will interpret the work. Still, she was willing for them to be called out in the context of this exhibition since other contexts will privilege other readings.

In a recent talk on the exhibition, Tom Gunning described these works as “promiscuous adaptations.”8 His phrase aptly suggests the ways that the artists have added layer upon layer of additional quotation, allusion, and invention without feeling duty-bound to focus their creative process—or our attention as viewers—on a singular point of origin. I don’t want to take the metaphor too far, but Gunning’s phrase suggests a kind of productive selfishness in which love for one source does not preclude desire for the simultaneous embrace of others. As Ben-Ner has noted, his primary allegiance is not to the source, but to the needs of his own work.

Fidelity, Part II

In his song “High Fidelity” Costello exploits the multiple meanings of fidelity by linking unfaithful romantic liaisons and the distorted transmission of sound. (The chorus is “can you hear me?”) This secondary meaning is particularly pertinent for an exhibition of video installations that rely on technology to reach viewers. In audio terms, “high fidelity” refers to equipment that transmits sound with little deviation from the original recording. In other words, the equipment provides an experience that is as faithful as possible to its source.

Before addressing this other meaning of fidelity, though, the phrase “video installation” needs a caveat. As technologies for creating and displaying moving images have improved and multiplied over the past century, artists have quickly found new uses for them, but terminology has often lagged behind. “New media,” “time-based work,” and “video art” are some of the most common recent descriptors, but none fully captures the complex ways that contemporary artists use technological tools. Arturo Herrera, for instance, made the images in Les Noces first as drawings and collages. He then photographed them using a still camera, worked with a computer programmer to create a software program that randomly selects sequences of these images that are then digitally projected onto opposite walls of a gallery. He prefers to call the work a “digital media installation.”

Still, I will continue to use the imperfect label “video installation” here since it usefully describes common attributes of the works in Adaptation: all contain moving images, are meant to be experienced over time, and assert an emphatic physical presence.

Since video installations rely in part on technology, they can be vulnerable to curatorial choices or institutional parameters around presentation. The meanings one takes from an encounter with, say, a sculpture in a museum is always inflected by its surroundings—the museum’s overall sensibility, the style of the display, the juxtapositions with other works of art in the gallery, the conceptual framework of the exhibition, and so on—as well as by the viewer’s own sensibilities. But while one’s response to the sculpture may shift depending on factors such as whether the work sits high on a pedestal or low on the floor, the intrinsic material qualities of the object itself remain essentially fixed. Not so with most video installations. To give just a few examples, a low-grade projector will dull the vibrancy of the image-making pixels that form the core of any video; an overlarge projection will diminish the power of an intimate work meant for a small monitor; a too-bright space will render images illegible; poor acoustic treatment will make sound inaudible. The material presence of a video installation thus depends in part on the quality of the technology used to display the work and the space it occupies, both of which will at least sometimes be outside the artist’s control.

To mitigate this potential problem, some artists have established precise conditions and equipment that they deem necessary for an uncompromised presentation of the work. Conversely, other artists embrace video’s malleability: they allow their works to be shown in a variety of display contexts that may then inflect the material experience and the meanings of the work itself. Video technologies offer artists a great range of options, so when consciously employed, the medium’s adaptability to both lo- and hi-fi presentations can be a great strength.

Eve Sussman & The Rufus Corporation’s The Rape of the Sabine Women (2006) occupies the “hi” end of that spectrum. This nearly feature-length video requires cinematic presentation within a black-box space that is acoustically prepped with a full multi-speaker sound system, a large screen, and seating. The audio treatment makes composer Jonathan Bepler’s carefully structured and pristinely recorded score an almost tangible presence, enhancing the percussive impact of footsteps amidst the Pergamon Museum’s silence, amplifying the steely threat of butcher knives brushed across one another, or infusing one’s body with the soaring soprano that weaves through the rumbling melee at the work’s end. The scale of the image also matters both in relation to a viewer’s body–the artists want it to be an absorptive expanse–and also in relation to its surroundings–it needs a room that feels spacious but doesn’t overwhelm the image. Because the artists want to control these elements of the work’s presentation, they are currently circulating it in two modes: as a limited-run or single-night screening in theaters, and in presentations like Adaptation in which a black-box space can be created within the museum.9 However, even with these controls, the artists cannot ensure a particular mode of viewing: casual museum visitors may choose to watch only a portion of the film or to start watching somewhere in the middle.

Catherine Sullivan, in contrast, has shown Triangle of Need (2007) in several quite different formats, including an eight-channel version that premiered at the Walker Art Center with projections, screens, and film arranged within a space divided by dark velvet curtains. In the version included in Adaptation, she condensed and remixed the larger work into three adjacent screens, with a separate fourth screen as an optional inclusion. This version has been shown in wildly different settings: first within Vizcaya Museum and Gardens—the opulent historic home in which Sullivan filmed much of Triangle of Need—and now in the Smart’s spare modernist galleries. Here, she placed colored gels over spotlights to turn the white cube ever-so-slightly green and thus subtly lay claim to the open space around her work.

Sullivan pays attention to details and they surely affect the ways that viewers respond to Triangle of Need. She does not, however, feel that her work requires any particular mode of presentation but rather believes that the work is supple enough to be presented in any circumstance. I pressed her on this point recently, thinking of how poor-quality equipment would diminish the visual impact of her beautiful long tracking shots and complexly orchestrated performances, and also of how images that fill one’s peripheral vision and depict her actors at something close to human scale usefully reiterate her work’s deep connections to theater. She adamantly insisted that we could watch Triangle of Need even on something as lo-fi and awkward as a trio of digital wristwatches and still have an absorbing and valid encounter with the work.10 Such flexibility of intention and presentation allows Sullivan’s work to live relatively comfortably in a variety of contexts.

Guy Ben-Ner’s Moby Dick (2000) is similarly flexible. His do-it-yourself production values can withstand low-fi presentations, and this work can live easily in different presentation formats although each may subtly inflect the work’s meanings. The artist prefers for this single-channel work to be projected or on a screen, for he feels that TV-style monitors overemphasize the domestic themes in his work at the expense of other meanings. Such display connotations are changing, though. In an age of relatively cheap plasma TVs proportioned according to the cinematic ratio, domestic associations may be outweighed by artistic ones, since such monitors were originally used to house the 1970s performance art videos that Ben-ner quotes in the piece. He agreed to show Moby Dick on a freestanding monitor for the Smart’s presentation of Adaptation.

Ben-Ner’s Wild Boy (2004) sets up more controlled and complex interactions among work, viewer, and setting. It can be shown as a simple projection. The work seems most complete, though, when embedded within its viewing platform: a simple drywall-and-plywood screen, a low green-carpeted floor that curves up to form a small hill, and a real tree with a projector nestled in its branches. Since the lower edge of the projection abuts the top of the platform, the viewer is placed not only into Ben-Ner’s version of “the wild”—a homespun bit of nature within the gallery’s realm of culture—but also into the fantasy-space of the video. The platform serves other purposes as well. Ben-Ner knows his work has to compete for attention (a perennial problem for time-based work), so in addition to luring viewers with his adorable children and the bits of slapstick that punctuate his videos, he also entices with a comfortable space to rest and watch. To return to fidelity, the self-contained design, the characteristically scrappy plywood aesthetic, and even the sound-absorbing carpet all help the work retain its aesthetic integrity within a variety of settings.

Arturo Herrera’s Les Noces (2007) has taken some time to settle into its current form. Ikon Gallery in the United Kingdom premiered a three-sided, six-channel projection with a fixed sequence of images. Herrera then reconceived the piece into this final diptych form. When restaged later, the piece will flex somewhat to fit spaces with different proportions and scales but will always retain this basic format, with a randomized sequence of Herrera’s images projected at a certain scale and level of brightness and occupying opposite walls of a gallery as the sound of Stravinsky’s score fills the space. It will shift slightly to accommodate new surroundings while retaining its central characteristics. This process returns us to the idea of adaptation but through a back door: another meaning of “adaptation” is the biological process through which an organism takes on characteristics that allow it to thrive within a changing environment.

So back to those needling questions: Are the works in this exhibition faithful adaptations? Does fidelity matter?

No and yes, yes and no. Fidelity of presentation certainly matters. It is, of course, crucial for institutions to respect display parameters defined by artists. Critics and scholars should also address video’s malleability and the ways that changes to the technologies and spaces used for video installations can inflect the work’s meanings in ways that may or may not be entirely controlled by the artist. Fidelity of adaptation, on the other hand, only matters if defined in loose and experimental ways. Unlike commercial film or conventional theater, contemporary art grants leeway for artists to simultaneously exploit an audience’s familiarity with a source and to eschew any expectation that an adaptation will honor that source. Artists have the freedom to play with their sources, to treat them simply as they would any other material, and this can yield powerful results. The works in Adaptation thus both embrace and throw into question time-honored traditions of making art based on other works. Unfurling over time, these extended meditations investigate, challenge, and amplify their sources. Distinct and complex, they remind us that the productive tension between fidelity and creativity—the central element of any adaptation—is a strong generative force in contemporary art.

NOTES